China has turned the nickel market on its head after the world’s biggest stainless-steel producer, Tsingshan Holding Group, this week agreed to supply about 100,000 tonnes of matte (containing approximately 65-75% nickel) to Huayou Cobalt and battery materials maker CNGR Advanced Material.

The news signals that the mainly Chinese-funded nickel pig iron (NPI) producers in Indonesia are now looking at making nickel matte, essentially giving the battery-materials manufacturers a new product to plug into their processes.

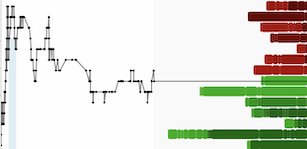

The market response was not pretty. London’s nickel prices fell nearly 9% on March 4 and in Shanghai dropped the most in nine months. The three-month nickel contract on the London Metal Exchange dropped as much as 8.5% to US$15,945 per tonne, its most significant intraday loss since December 2016.

According to Bloomberg data, the most-traded June nickel contract on the Shanghai Futures Exchange ended 6% lower at US$20,180.61 per tonne, posting its most significant intraday loss since May 2020.

Ironically, nickel price benchmarks were trading at a six-year high as recently as the last week of February on expectations that swelling demand from the electric-vehicle sector is set to create a substantial shortage in nickel suitable for EV batteries. In February, Tesla’s Elon Musk even said on Twitter that access to nickel was the EV maker’s top concern.

News that Norilsk Nickel expects to stabilize flooding issues at its Oktyabrsky and Taimyrsky mines in the second week of March, also weighed on nickel’s immediate price outlook, as well as an Indian trading group liquidating an LME metal position, but Tsingshan is the real story here.

Many investors may be shaking their heads right now, recalling that in 2007 China gutted nickel prices by rapidly flooding the market with cheap NPI material to feed its rampant stainless steel industry. On the surface, this looks like a repeat of history but this time it’s battery-grade nickel to feed the rapid growth of China’s EV industry. There are nuances here, however, that speak to a bigger, more complicated picture.

Firstly, let us look at the production process. In recent years, the Chinese have decided to make their own nickel from laterite ores to feed the stainless steel beast, creating a huge supply of nickel in the form of NPI. One cannot use NPI or ferronickel directly for battery material since the high iron content is like a poison to batteries. By making nickel matte (which is essentially a nickel sulphide with some impurities), they can make a nickel-bearing material that can then be fed into cathode manufacturing for EVs.

The Chinese now propose to convert some of the lowest-grade forms of nickel (NPI) into nickel matte. NPI generally contains about 5-15% nickel as opposed to ferronickel, which clocks at anything from 15-50% nickel, and nickel matte at 65-75% nickel.

The process of making nickel matte from NPI is not new. It involves a further pyrometallurgical step where one adds heat and sulphur, and the end-product is purer nickel (the matte) with less than 5% iron or impurities. This product can then be plugged into the same market segment as nickel sulphide mine concentrates or nickel matte made from traditional smelting of nickel concentrates.

Chinese NPI production costs range between US$3.50-$4.50 per lb, and we estimate that making nickel matte could add an estimated US$2 per lb, the sum still being less than the current nickel price. However with NPI and matte both receiving approximately 85% of LME price in sales, the additional cost of making matte from NPI translates into an LME price of US$7.60 per lb as a break-even cost for production. One has to question why NPI producers would add cost to receive the same revenue and reduced profit?

The processing is highly energy-intensive and highly pollutant, costing as much as US$5,000 per tonne of nickel more than a nickel sulphide operation and adds to the GHG intensity of NPI production which is already the highest in the nickel industry. According to Wood Mackenzie, NPI production has an intensity ranging from 40-90 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalent per tonne of nickel produced as NPI. The added processing will only add to this intensity and also introduce sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions into the equation. In comparison traditional sulphide mines typically emit less than 10 tCO2e/t of nickel and HPAL(high pressure acid leach) processing of laterites is typically less than 40 tCO2e/t of nickel. Wood Mackenzie estimates that the nickel industry average is approximately 36 tCO2e/t of nickel (as refined metal).

That could easily translate to a total carbon footprint of 80-100 tCO2e/t of nickel produced. To give some real world context: At those levels, and with the type of atmospheric emissions involved, the local regions could even end up with acid rain. We have not even touched on the particulate matter pollution created by pyrometallurgical operations such as NPI and ferro-nickel (FeNi). In comparison, an HPAL operation such as Ramu in New Caledonia makes about 16 tCO2e/t of nickel.

Putting aside the irony of embracing a highly pollutant process to supply feed material to a climate friendly end-product (EVs), I want to look at why this is happening now. After all, China has invested serious sums of money in new HPAL operations. Why not rely on those new operations?

The biggest and most likely issue here is, China is probably producing and consuming a lot more batteries than Western experts and observers currently believe, and planning to ramp that consumption beyond current expectations on an accelerated timeline, hence the urgency to procure new sources of feed material.

And that’s just for domestic use. With its acquisitions of battery metal supply and processing capabilities, China doesn’t just want a robust domestic market, it intends to dominate the world market. They have the opportunity here to end up with a double-win, which is to reduce nickel prices for long enough to put off Western investment in new nickel production so that Western manufacturers will have no choice but to be utterly reliant on Chinese materials and Chinese batteries. China wants to be the “Silicon Valley” or modern Detroit for batteries, electric vehicles and the related supply chain as a whole.

When one considers Indonesia’s primary sources of power, heavy fuel oil and coal, it quickly becomes apparent that these Indonesian HPAL plants will deliver what amounts to some of the dirtiest battery-making ingredients produced anywhere.

Of course, with the Tsingshan deal, China is essentially trading the environmentally problematic operations of HPAL being constructed in Indonesia (huge quantities of solid/liquid tailings need to be addressed) for expensive, harmful air emissions. With the increasingly ESG-conscious Western market that would be expected to cause pushback from manufacturers and consumers, but then again, these new matte units are not destined for the rest of the world, even though they impact the global market.

This makes nickel sulphide development projects like those found in Western Australia and like Giga Metals’ Turnagain project in Canada so attractive, with their straightforward metallurgy and low carbon intensity per tonne nickel produced.

It is going to be interesting to see how the rest of the world responds to this past the initial price shock of the past week. China’s move to accelerate their plans to produce an expensive nickel matte seems to indicate that battery and also EV demand is going to outstrip even the most ambitious current growth estimates in China and throughout the world, and that means more and more battery grade nickel is needed.

Governments and automakers have largely left the fast-approaching problem of battery metal supply to the mining industry to solve. China’s continued fast, strategic moves suggest a more proactive approach is needed soon unless the West is content to cede the green technology and transport revolution to China’s growing industry.

Perhaps the recent announcement by Tesla to assist the owners of the New Caledonia nickel mine is evidence of change. However, Tesla is also in discussions to construct facilities in Indonesia in order to access this cheap source of nickel. With Tesla asking the market for ESG friendly nickel, one has to wonder what the real driver for their decision is.

For those who may be more focused on the nickel price moves, let me leave you with two final considerations: Some observers have suggested that Tsingshan signed this deal because of an apparent shortage of the ability to dissolve metallic nickel to make nickel sulphate for batteries. Indeed, if one can refine matte to nickel sulphate, one can dissolve nickel into nickel sulphate like BHP is doing in Kwinana, Australia. However, the deal gives a false sense of security that the output of nickel sulphate will increase, when in fact, it will just provide the midstream market more raw materials from which to choose.

Lastly, the NPI that China is using for the nickel matte production is not new supply. They are simply taking from the stainless steel industry and giving to the battery industry — at great cost in energy and emissions. However you look at it, we still need a lot more nickel production if we are going to transition to electric vehicles.