By Keith Schaefer, Editor, Oil and Gas Investments Bulletin

How badly do oil producers want to transition out of the deepwater and focus on shale? And guess what that means for the global oil price?

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM) just paid Seadrill (NYSE:SDRL) $125 million in cash to get out of its commitment to use the West Capella drillship.

Don’t you wish someone would just pay you $125 million to pack up your things and just go home?

The contract that Exxon had on the Seadrill had an expiry date of April 2017. Exxon couldn’t wait that long and instead elected to pay the equivalent of $370,000 per day to just get out of the deal.

Had Exxon used the West Capella it would have been paying $627,500 per day.

This is not a decision that is unique to Exxon. The theme of shifting away from offshore projects is a consistent way across oil and gas producers.

Conoco Phillips – Last year the company said it is done with deepwater exploration forever.

Marathon Oil - Announced that all of its budget in 2016 will be directed to its onshore resource plays with only $30 million that was previously committed to going to offshore work.

Chevron – Is pivoting in a major way away from big ticket offshore projects and is hoping to ramp shale output up to 25% of the company’s production by the middle of the next decade.

This list goes on and on. And this, dear reader, will almost single-handedly move the oil price higher in the coming two years.

Last August the U.S. federal government held an auction for offshore oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico. Just five companies submitted bids and only 33 leases were sold. This was the worst showing in three decades for the Western Gulf of Mexico.

Offshore Oil Production By The Numbers

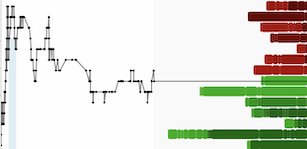

Offshore production accounts for 30% of total global oil production. The percentage of global production has remained the same since the early 2000s but the absolute amount of production has grown.

Today nearly 22 million barrels of oil per day is produced offshore; the figure in the chart above includes all liquids.

Offshore production has lower decline rates than shale does, but considerably higher decline rates than onshore vertical developments.

It is hard to pinpoint these decline rates exactly since each field is unique unto itself. What the industry generally believes is that offshore production declines at twice the rate of conventional onshore.

That would put the offshore decline rate somewhere between 15-20% per year. These higher decline rates mean that the sudden halt to offshore development will result in BIG offshore production declines.

Off a 22 million barrel per day production base—15-20%= 3.3-4.4 million barrels a day—gone. That is substantially more than the spare capacity of OPEC right now. That means that in just one year, the world oil supply could be put into deep undersupply (pardon the pun) as offshore exploration and development stagnate.

Short Lead Time, No Exploration Risk

Shale/tight oil has beat offshore production in every way. Onshore costs are down dramatically. The time it takes to drill onshore wells is down. Onshore flow rates have improved.

But is isn’t just about breakeven-costs. There are other considerations.

Going offshore involves taking exploration risk. With shale, companies know they’ll get a producing well every time they drill. You can imagine how many companies can afford to throw money down dry holes these days.

Even if an offshore exploration well is successful there are drawbacks.

Once a discovery is made offshore companies need to sink huge sums of money (often billions) over an extended time period (years) before any production can happen. That leaves companies without any revenue from the money being spent for long stretches and also exposes them to commodity price swings.

Just imagine giving the thumbs up to a billion dollar offshore project that needs $70 per barrel oil and then having to watch oil crash just as production comes on stream.

Shale oil wells can be drilled in weeks meaning that there is very little time between investment and cash flow. A shale well also costs under $10 million and can’t ruin a company like a billion dollar offshore project.

The location of shale within the continental United States is also far superior than being in the middle of the ocean. Pipelines are already in place onshore, employees can go home to their families every night and the worst case accident scenario is much lessened.

Shale is simply a better option than deepwater development. It is lower risk and has become higher return.

What Would It Take To Get

The Industry Interested In The Deepwater Again

The majority of the oil and gas sector is in serious financial difficulty. It will take a long stretch of sustained high oil prices before anyone gets bullish on deepwater exploration again.

Existing discoveries will be developed. Investing money in those situations provides a guaranteed return on investment through cash flow. Wildcat deepwater exploration is not a business that is coming back for a long time, if ever.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to open the taps has changed this business for everyone. The idea that sustained high oil prices were the norm for the future is gone. Volatility is back and it isn’t going away.

There is no safety valve for oil prices. It is everyone for themselves from this point forward.

Shale oil offers a predictable, manufacturing-like business model around which companies can plan. And it can be stopped and started on a dime depending on oil prices.

Ten years ago shale oil wasn’t even on the radar. Now it is has displaced the deepwater which was once thought to be our only savior from peak oil.

Now….about those electric cars.

Keith Schaefer