By Peter @Newton Bell, 15 December 2016

It is my pleasure to provide you with a transcript of an extensive conversation that I had with Mr. Doug Ramshaw, Director of Vendetta Mining (TSXV:VTT). The company has received some positive attention recently, which I think is well-deserved because they are working hard to execute a clear business plan. Simply put, they acquired a misunderstood asset in a prolific mining region and are showing that it has much more potential than previously thought. Read on to find out all the details!

>>

D: When we found the Pegmont project, we had been looking at zinc assets for years. Going back to 2012, we did high-level studies of 30 or 40 projects. We looked at over 80 different projects.

D: This one was brought to our attention by Peter Voulgaris, a mining engineer and geologist -- Australian born and raised. He had worked in the area and knew the project. One of the things that we decided, quite some time ago, was that we wanted to look at development stage projects. We weren’t interested in trying to make grassroots discoveries because it’s costly, the odds are very much against you, and a lot of the low hanging fruit has been taken. With the exploration cycles we’ve had in the past, the easy stuff has been found.

D: We looked at a project that had been found in the past to see if it had been misinterpreted or if there was some different approach we could take. People who are close to a deal often can’t see the woods for the trees. So, we were able to take a fresh look at a project that, in our opinion, had been misinterpreted for many a year. The work that we have done over the last couple of years has really justified that approach to Pegmont.

D: There is another thing that we think is crucial, especially in the zinc market. You can have multiple exit strategies, but the top of your list shouldn’t be “we are going to mine this ourselves.”

P: (laughs)

D: There are explorers and developers, and then there are the miners. That’s why you don’t see many small cap exploration companies turn into small mining companies – it’s generally not the right skillset. In order to take advantage of what we expected to see happening in the zinc market, we wanted to find an asset with a number of clear potential exit paths.

D: A big value-add for us with Pegmont was its location. It is not just that it is in Australia, which is a very strong mining jurisdiction, Pegmont is surrounded by every bit of infrastructure you could possibly want: it is within 20KM of two existing mines and mills, it is a few kilometers off the main road network, there are gas pipelines in the area, there are concentrate-handling facilities at the end of railway lines that were established to service smelters that are on the coast at export facilities. Everything you could possibly want surrounds Pegmont, so that was a huge part. But you’ve still got to have a project. You can have the best location in the world but, unless you have a project that makes sense, all that infrastructure is for naught.

D: Pegmont was actually discovered in the early ‘70s at a time when the typical lead-zinc grades of projects that were being developed in that part of Queensland were above 15% combined lead-zinc. Pegmont was believed to be a single lens, lead-dominant system. All the historical exploration in the upper part of the deposit was proving that concept. The lead-zinc ratios were 2.5:1 or even 3:1. It didn’t have the silver credit that other operations up there have and, as such, it lay dormant.

D: When we looked at it, our technical team saw the potential for this to be a more standard ‘Broken Hill’ style deposit, where you can have multiple lenses. As you vector towards the original source of mineralization, you see an increase in the zinc grade and an overall increase in the zinc-lead ratio. Some historical holes indicated that was likely to be the case, but they hadn’t been followed up on -- certainly not to the extent of our program.

D: We acquired this option on the project in late 2014. We were backed by Resource Capital Fund out of Denver, who invested and acquired 28% of the company. That allowed us to start an initial drill program and prove our theory, a theory that we have further confirmed with a lot more drilling this last year. We headed down-dip from the upper part of the deposit, which were Zones 1, 2, 3 and 4, and we hit multiple stacked lenses and saw an increase in the zinc-lead ratio in zinc’s favour. That is what we expected to see and consider that to be significant progress.

D: The initial resource was about 5.3 million tonnes grading 9.25% combined lead-zinc. That was established on the upper part of the deposit, Zones 1-4 with a 2.5:1 lead-zinc ratio. We only really look at the sulphide portion of the deposit as it’s what we are interested in –- it’s what our potential end-users would be interested in. As we’ve started to drill off Zone 5, we have started to see grades which surpass the upper part of the deposit and, more importantly for us, zinc grades that are approaching 1:1 with lead; in some cases we are even seeing as much as 2:1 zinc to lead in the lower part of the deposit.

D: We have completed over 13,500 meters of drilling in the last couple years. We are big believers that slow and steady wins the race, perhaps to the chagrin of our shareholders at times. We’ve committed the money that we’ve raised into aggressive drill programs -– getting it into the ground. You can market a company all you want but, if the project itself hasn’t been advanced to the point where it can take advantage of the lead-zinc cycle then whatever stock price you have will be unsupported. It’s quite important to advance the project to support the stock price. We’ve started to improve our marketing efforts. To date, it’s really been a focus on getting as much drilling done as possible.

D: We’re fortunate that drilling costs in Australia are very low. If we factor all costs into our drilling, it’s probably around $200/meter. That’s fully loaded. The direct costs for the pre-collar RC are around $40/meter to get down to the near the mineralized horizons, and then our core drilling costs are around $110-$130/meter. It makes for very economical drilling.

D: Track-mounted drill rigs driving around what is typically very flat Australian outback. We’re not dealing with helicopters and the costs of drilling in the Great White North, which rise quickly when you’re drilling on the side of a mountain.

P: Yup! So, I’m looking at the geological model there and I see the cross section of Zones 1-4.

D: We’ve projected hypothetically onto that cross section, based on our geological model of the Pegmont deposit.

D: We’ve also shown what we expect to see from Zone 5, based on our geological model. Sure enough, we’re seeing that the results are meeting our expectations in Zone 5, which is an increase in the zinc ratio and an increase overall in grades. The historic resource in Zones 1-4 was thought to be a lead-dominant system with a single lens, but we saw an opportunity to show that it also has multiple lenses with a significant amount of zinc as I previously mentioned.

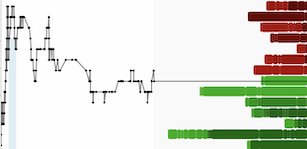

D: We talked in an earlier piece about how the zinc market is looking very positive, and the fact is that lead and zinc tend to follow each other hand-in-hand. I think zinc will lead the way this time, but we’ve seen lead catch up to zinc lately. Both metals have outperformed their peers over this last year.

D: And a key feature of the Pegmont project is that it is almost entirely zinc and lead. When we’re speaking of things in a zinc-equivalent grade, it’s not comprised of other metals. That matters because the other metals may not necessarily follow suit. It’s subtle, but it’s very important. If you have a zinc-equivalent grade where your zinc-lead component is only half of your overall grade, then you have to look at the other metals and ask if those are going to be moving the same way as zinc and lead? If it’s not the case, then maybe that project doesn’t have the same leverage to the metals market that we feel a pure lead-zinc project like Pegmont has. Now, you could argue that this project would be better if it had more of a silver credit, but then it might not have been available to us in the first place! You have to be careful what you wish for. The opportunity for us to acquire Pegmont became available because it was seen as a lead-rich system with limited silver credit, as opposed to what we have been able to identify it as.

P: Well, the terms that you got this property for were pretty good.

D: We like to think so, particularly for something that had as much work done on it as it did.

D: Going back to our strategy of looking for development stage assets that had multiple potential exit routes – we felt that we inherited a tremendous mineral package with an established resource and lots of upside for pretty favourable earn-in terms. From the start, we looked at this from the perspective of a potential acquirer. By the time this project is at a production decision, hopefully in a zinc bull market, the back-end advanced royalty payments will be of consequence to the acquirer. When we negotiated the deal, it was very important to consider proposed deal terms from the other side. We did not want to limit our ability on the M&A side. We needed to have something that was not just an acceptable earn-in for us, but also gave acceptable terms for any potential incoming group.

P: Well, the 1.5% NSR or run of mine royalty don’t seem particularly onerous. Are there other payments due on the back end?

D: There is a final cash payment of $1M due on transferring the licenses into our name and an advanced royalty payment of $3 million that goes to the three grandfathered mining permits, which covered the large part of Zones 1-4 and the broader exploration permits. All cash payments are ultimately offset against any royalty payments until they are recovered. We anticipated developing a project that we were not going to mine ourselves but was going to be of consequence to someone coming in. We didn’t find the royalty terms overly egregious.

P: Great. Well, the favourable earn in terms fits nicely with the idea that you were bringing a different interpretation of the geology there. I am curious what is behind the horizontal, banded formations in the Broken Hill model?

D: If you picture those national geographic documentaries of the black smokers on the ocean floor, they are spewing out all manner of metal content. Take yourself back in geological time to a basin-like environment where there is that kind of black smoker on the ocean floor, releasing pulses of mineralization over a geological timeline. Those pulses were deposited on top of the basin floor, then overlaid with sediments, again and again. The Cannington mine, which is 20KM away – you can actually see their headframe from our deposit – was one of the largest lead-zinc and, in fact, silver mines. It had a tremendous silver grade that, sadly, we don’t have. I think they mined from about six of these banded formations. It’s a sedimentary environment with a black smoker providing depositional material in various layers.

P: Is the mineralization incoming through that sedimentary rock, there?

D: No, the metal is deposited after a pulse from the smoker and then sediments from erosional environments around this ocean basin are overlain. Then it pulses again and more sedimentary deposition occurs. It’s not an intrusion, it’s laid down at the pulse of mineralization in a basinal environment.

P: Oh, OK – I think I understand that now, thanks. That sounds like a very different geological model from anything I have heard of before. What is the host rock like, then?

D: Well, we are very fortunate. The actual mineralization is hosted in banded iron stone and the high-grade metamorphism of the region means that the BIF, the banded iron formations, are hosted within a very competent quartzite. That’s key, in terms of ground conditions. With what we would expect to be a suitable mining method for this deposit, should it ever come to that point, the competency of the wall rock is very important in terms of extraction costs and the ability to extract as much as possible. We are very fortunate in that regard.

P: Even though it’s a sedimentary rock, it’s still solid?

D: Yes -- it’s metamorphosed sediments, which in our case lends itself to being very solid.

P: Cool! I haven’t heard about an underwater volcano depositing mineralization in that way before. I am more familiar with basic intrusive deposits.

D: It’s a classical kind of geological model. If I’m right, then the Broken Hill model is a subset of the sedex deposit type, which stands for sedimentary exhalative. We are surrounded, in that region, with a number of world-class examples, such as Cannington. This doesn’t have the tonnage scale of a project like that, but it is easy to point to other examples in the area. When you’re trying to present a narrative as to what your project is and how it fits into a regional perspective, it is nice to be able to point to regional analogues.

P: As you move down dip, I wonder if the scale could expand in a significant way.

D: You’re always trying to vector towards the source. We think we understand the vector of mineralization down-dip. Our tenements extend a further 2KM to the south of our drilling, so we’re not caught in a situation where we are up against our property boundaries. We’re quite fortunate in that regard, as well.

D: In fact, we feel that we only need to focus on tonnage in the known mineralization rather than having to step out to get to tonnage levels that the project would need. That’s fortuitous, as well. Even with cheap exploration costs, Mother Nature can play some tricky games with you. If you don’t have to do too much in the way of step out drilling – into the unknown – it’s more favourable.

D: In fact, the couple of places where we have stepped out were some of our best holes. That is one of the holes in the last release and hole 17 from last year’s program, which were probably the only two holes outside of the known boundaries of mineralization. This is definitely an area that we will want to follow up on, but we’re quite comfortable that we can get to the necessary tonnage just within areas of known mineralization. None of the Zone 5 mineralization that we’ve been focusing on or the near-surface Burke Hinge Zone have been included in the historical NI 43-101 resource estimate. Those will be our first areas for incorporating into an updated resource model.

P: Looking at the original zones there, I see that dyke below and I wonder if it is reasonable to expect that there may additional layers of the iron bands below the known one?

D: In the upper part of the deposit, we think that the earlier interpretation was correct.

D: It’s a single lens at that point, as you become more distal from the source. As we’ve gone down dip, we’re starting to see the second and third lenses. One hole even intersected a limited example of what may be a fourth lens! Of the three lenses we’ve identified in Zone 5, two of them seem to be the ones that carry though. The upper lens – not so much. I think the potential is more down dip from Zone 5, rather than looking below the main lens in the upper part of the deposit.

P: I can see the implied continuity, north-south, in the diagram, but I wonder if these things extend fairly far horizontally, east-west, as well?

D: You’re going to see some grade difference, but the actual continuity of the host structure is pretty good over the scale of the deposit. We’re talking about an east-west strike length of the upper part of the deposit that is +1.5KM across. This isn’t necessarily something that is 100M thick –- a lens that might be carrying mineralization may be 4-5M thick –- but that is more than adequate mineralized thickness from a point of view of the underground mining methods that one might chose to employ, should you develop a sufficient resource.

P: You start to get to a relatively deep level with Zone 5, 200M below surface. That’s not a huge depth, but I wonder if you have any comments on the depth. Any increase in cost in drilling or anything?

D: Not really. The direct costs for core drilling vary between $110 and $130, depending on depth. It doesn’t go up dramatically.

D: The identification of near-surface sulphides at Burke Hinge Zone was great.

D: The sulphides start within 25M of surface. The Zone 5 depth, itself, is not particularly deep. Especially since any development of this deposit would be through an underground mine, where you start in the upper parts of the deposit and then work down through the ore zone. You’re not talking about something that is particularly tough from an exploration or potential future mining perspective.

P: A question about other, similar mines in the area. Is there any sense that those resources got significantly larger as they were drilled to a greater depth?

D: That’s a good question. What I can speak to is the Cannington mine – they started with a silver head grade that was over 400 grams per tonne. It was almost more of a silver-lead mine than a zinc one. They had a particular zone there that was the focus of much of their mining in the early part of its life. The grades at Cannington are actually lower now than we believe our head grades would be, as they have exhausted a lot of the higher grade lead-silver areas of their deposit. From a regional perspective, Pegmont doesn’t compare to the tonnages of other mines in the area, at least from what we’ve defined so far, but we believe it has the scale to achieve the economic goals that attracted us to it and will attract interest in a rising zinc market.

P: Looking at the table here, I see that Cannington has an open pit marked at 20 million tonnes and an underground section at 67 million tonnes.

D: Yes, you have some large mines in the area. Again, you can see the silver grade has declined there too. We’re seeing, industry-wide, a declining grade curve for lead-zinc operations. There is a dramatic decline in head grade for lead-zinc. If we can be in this 9-10% range, then we think we can become pretty interesting to the regional make up of lead-zinc production in Queensland.

P: Looking back at your 2014 resource estimates, you’re at 6% lead and 2.7% zinc in the sulphide zone and now seeing grades increase.

D: The historical resource comprises portions of Zones 1-4 and that’s the area that is +6% lead and +2% zinc, which gives the 9.25% combined lead-zinc grade. When we’re down in Zone 5, we’re seeing grades that are more 50:50 on the lead-zinc makeup.

D: As we increase tonnage for this project in Zone 5 with the multiple lenses and higher overall zinc grades, the overall lead-zinc ratio of our resource model will to become more zinc friendly.

D: Again, both of our metals have historically tracked each other to some extent and stand to benefit greatly as we move through the next cycle in lead and zinc markets. One has to remember that a lot of these zinc mines that are coming offline are zinc-lead mines, not primarily zinc mines. When you’re seeing production come offline from what is perceived to be one of the top zinc mines in the world, it’s also curtailing lead production as well. We’re very comfortable that 99% of our metal value is attributed to lead and zinc, regardless of ratio.

P: Looking at the Burke Hinge Zone again -– it’s interesting to see it in the North-East area, extending out from Zone 2. Maybe that is not surprising to see that so close to surface out there, stretching away from the deeper mineralization at Zone 5 and the amphibolite dyke providing some kind of a boundary.

D: Even when we think that we totally understand the spatial and structural connotations of Zone 5, we can still drill the odd hole down there where we’re missing a structure that we would have expected to hit at a certain point. Sometimes Mother Nature throws a bit of a curveball. At the Burke Hinge zone, it’s a positive curveball.

D: Some of our future drilling will be to target what we call a Bridge Zone between Burke Hinge and the upper parts of Zone 1 and 2. What we tend to see throughout the deposit is that there is not much in the way of structure, from a point of view of faulting.

D: We’re seeing greater concentrations of metals on fold hinges, which is pretty standard. Then, as you get onto the limbs of those folds, you can see a depletion. We’re not sure about the Bridge Zone – we’re pretty sure the structure is there, but it is as yet unclear whether the concentration of metal has happened there. The flat-lying Bridge Zone between the two areas of folding, Burke Hinge and the upper parts of Zone 1 and 2, might be more depleted. It will be another area that we will drill test in time.

D: We also think that there could be other Burke Hinge Zone-like targets that run around that amphibolite in the upper part of the deposit. Those are luxuries for us because we don’t really need to go out prospecting for new targets, as we feel like the existing confines of mineralization provide our target tonnage.

P: Looking at that Bridge Zone, I see one hole on the edge of Zone 2, hole 127, and it is 10% lead. That is fairly rich.

D: And close to surface. Our internal engineering study has indicated that Burke Hinge Zone could optimize to a starter pit. That could be the engine that drives the development of this project. That’s nice because it is located on grandfathered mining leases.

D: Permitting –- every project has permitting issues. One has to anticipate those. We are fortunate to have those grandfathered mining licenses. There would need to be environmental work done, but the Dugald River Project in Queensland, which was a $1.6B project, took 18 months to permit. I think that speaks to the favourable mining jurisdiction, which was a key feature of Pegmont for us.

P: Any comment on all this folding? The geological model would suggest to me that the bands are deposited in a relatively flat way, but I guess there is some pressure being applied somewhere along the geological timeline.

D: There is a large granitoid unit to the north and its emplacement probably had something to do with the folding. You’re right –- it is that kind of feature that would create some of that structural folding. That pink at the top of the map, there.

P: Oh, I see -- that looks like fairly large intrusion there. And granite! And what about the Bonanza Lode out there, any comment on what that was?

D: It could be something similar to the Burke Hinge Zone, a folded zone of near-surface mineralization. It’s a future target for us or someone else. I’m not sure if it’s something we need to chase, to be honest. But it’s something which is akin to what we’ve been targeting at Burke Hinge. We think there is potential for similar near-surface targets, although all of the deposit is really near surface by most mining standards.

P: That is interesting because it seems, to me, that these are metals are often found in much deeper deposits.

D: Well, they can be. It’s not the case that all lead-zinc is deep. But, I think you can say with most commodities these days, if you want to be looking for deposits in good jurisdictions then the low-hanging fruit has already been found. You have to look for something deeper. That’s what was so nice about us reinterpreting the Pegmont deposit and understanding it for what it really was.

P: And that reinterpretation, was that mostly your doing or were the vendors of the project thinking along a similar line?

D: The vendors were looking at the oxide mineralization and seeing if there was something that could be done with that near-surface lead-oxide. We had absolutely zero interest in oxide mineralization.

D: A lot of companies had proceeded and just looked at the upper parts of this deposit. I think one company had optioned it just prior to the Global Financial Crisis and were probably looking along the right lines, but the GFC came along and scuttled their efforts. They were potentially in a similar place to where we are now, in terms of identifying it for what it actually is.

P: It seems like that oxide zone has some pretty thick hits in Zone 1, but they are distant and final expressions of those bands.

D: I think it helps to show the scale of the mineralization. That is what was so pleasing about Burke Hinge: to find sulphide mineralization so near surface. The sulphide has better metallurgy. There are only a couple smelters in the world that deal in the oxide zinc. Our mandate was always to look for sulphide mineralization. It was a very pleasing discovery to demonstrate that near-surface sulphides exist, such as Burke Hinge Zone. We think, from an economic point of view, that Burke Hinge could be a real driver for the project, potentially.

P: And the type of mineralization you’re finding now, can that be processed by the smelters nearby?

D: Historically, the only work that had been done on the project from a metallurgical point of view was a bulk concentrate test. It yielded great recovery of both metals in a bulk concentrate. When dealing with lead-zinc deposits, you need to be able to demonstrate that you can float what is referred to as “differential con”, which is effectively one zinc concentrate and another lead concentrate.

D: If there was an Achilles Heel to this project, it is that we still don’t have that answer. You can have a slew of expert witnesses come and testify that there should be no issue with producing the differential con, but you still need to prove it. We’re actually conducting the metallurgical work right now because we want to address that from a public point of view.

D: The smelters that exist in Australia -– there are two to the south owned by Nyrstar. One is a lead smelter, one is a zinc smelter. The one on the coast, accessible by rail from Pegmont, is Sun Metals, which is owned by Korea Zinc. There is a zinc smelter at Townsville and a lead smelter at Mt. Isa. You can see from how I’m naming those that you’re sending lead con to one and zinc con to the other. We always identified that as a key area that we want check off: to demonstrate that metallurgical testing has been done. Those results should be back to us early in January. That, coupled with our drilling, will serve to update the resource model for the project in the early part of 2017.

P: Are those smelters generally open to taking ore from various other mines? They are not dedicated to processing their own production.

D: Yes, short answer. In many cases, a smelter is interested in the end product. They’re not necessarily miners, they’re smelters.

D: An interesting point that we didn’t cover when we were discussing the lead-zinc market is what are called TC/RC’s –- treatment charges and refining charges. They probably give one of the best data points for the current state of the zinc mining market. You can look at days of mine inventories and potential deficits on the mine side, but TCRCs really give an indication of tightness in the metals markets. They are the price you have to pay the smelter to effectively treat and refine your concentrates into end-use metal. When mines are producing concentrate left, right, and center, the TCRCs will favour the smelters. They don’t need to take your con, they can take con from anywhere.

D: Typically around February or March each year, Teck and Korea Zinc will negotiate their TCRCs for the year. It’s a bit of industry bellwether, as others will tend to follow suit. At the beginning of 2015, those TCRCs were agreed in the range of $240/tonne. Back in early 2016, we heard that the smelters wanted to lock in those TCRCs for three years. That should tell you everything about where they could see the concentration market going. This year those TCRCs dropped to about $205-210/tonne. And what’s really interesting is that the spot TCRC market has dropped to around $100/tonne – it’s really showing a tightening. When you start getting to those levels, the market conditions are favouring the miners. These smelters want to stay at capacity and are reducing their treatment and refining charges to attract the concentrate that they can refine into end-use metal.

P: Good news if you can get a small starter pit at Burke Hinge! I don’t know how along those prices will be around for.

D: Well, again, we’re not miners. I think one could say that Australia has an efficient contract mining landscape. One could, perhaps more realistically than in some situations, wave the flag and say “oh, we’re going to do this ourselves” but is often treated with some derision by the market. And rightfully so!

D: We’re not portraying ourselves as miners here. Our goal is to develop an asset that, hopefully, has all the characteristics that make it attractive for someone who does want to mine it. At that point, all the benefits of the infrastructure, all the benefits of potential smelters, and the benefits of what we believe could be a smooth path on the permitting side, if there is such a thing, will come into play for someone else.

P: I’m afraid I’ve jumped around a bit here and haven’t really followed your presentation deck. Are there any other remarks you would like to make based on the presentation here?

D: Yes, thanks. To begin with, we have that historical resource. Since acquiring the option for this project, we’ve done a little over 13,000 meters of drilling. None of that is included in the resource update. None of Zone 5, which still needs more drilling, is included in the resource update. None of the Burke Hinge Zone is, either. We’re anticipating to update the resource model in Q1 of next year, alongside met work.

D: It’s hard to draw peer group comparables when you’re working off a historical resource that doesn’t have a clear peer group but, as we start approaching 10 million tonnes of material, it becomes easier to make those comparisons. At that point, a lot of the advantages of Pegmont come to the fore.

D: When you start comparing apples-apples, you realize “wow, these guy’s don’t have infrastructure challenges and the like.” Our goal is to continue with what we’re doing, which is a very focused reinterpretation of what could be a significant zinc-lead mine for someone else.

D: To speak a bit to the structure of the company, we got the first program done with RCF’s backing. Coming into this year we had 22 million shares out. Management and RCF owned close to 50% of those. Maybe we were a victim of being too tight but, more than anything, we were a victim of trying to advance something in a market that wasn’t listening. It wasn’t listening to any commodity, let’s face it. Things turned around this year and we bit the bullet with an equity financing. We knew that this project needed to be advanced on a certain timeline to take advantage of a lead-zinc market, not to take advantage of promoting ourselves in a rising lead-zinc market.

D: We bit the bullet and did a financing earlier this year and our shares out went from 22 million to 72 million. The reality is that it was more of a quasi-rights offering. Of that $2.5M that we raised at $0.05 per share, which included a full warrant at $0.10, 60% of that was taken down by management, Resource Capital Funds, who maintained their position, Soliatrio Exploration Royalty, which is a Toronto and New York listed lead-zinc company that has a great asset down in Peru that took just under a 10% stake, and some Australian funds as well. Whilst we have been eating some paper over the last months – you can think the stock is in the safest possible hands, but you’re always going to have some selling – I think we’ve done a good job in a tough market to clear up that. The overhang isn’t as bad as one would normally expect with a company doing a five cent financing because so much of that went into the hands of existing institutions and management.

D: The goal, now, is to advance the project to PEA by Q1 2018 and, at that point, to demonstrate on a public stage what we have already internalized. If we can hit our tonnage goals, then the economics of this project can be very attractive. Between now and then we need to do that work, demonstrate the metallurgical work, and continue to prove-up the tonnage on the back of the resource update in Q1. We will aggressively drill to try and coincide that PEA with what we believe will be the heart of this next cycle in lead and zinc.

P: Great.

D: And we’ve been very fortunate with the team that we’ve been able to attract. Our CEO, Michael Williams, had successes with Adrian Fleming and Rob Mcleod in founding Underworld Resources. Their White Gold discovery helped kickstart the Yukon gold boom back in the earlier part of this decade. Underworld got bought out by Kinross. Peter Voulgaris worked for Robert Friedland for 7 years including 5 at Oyu Tolgoi in Mongolia, where he was technical services manager, and he has great experience working with the majors. Recently, a former colleague of his from Ivanhoe, David Baker, joined the Board.

D: We’re excited to continue to add strong people like Doug Flegg, who had ten or eleven years with BMO and finished his BMO career as head of mining sales, where he was involved in $25B worth of transactions. People always say “Management is key” and they’re absolutely right. I am very encouraged with the corporate side of the company thus far.

P: Wow, looks like you are well positioned for some discussions with majors there. Thanks very much for walking me through the basic presentation here, Doug.

D: My pleasure, Peter. See you on CEO.CA!

.jpg)